Ally Baldwin, M.Ed.

According to ACPA and NASPA, “Higher education is a dynamic enterprise facing unprecedented change,” (2015, pp. 7). We can see this all around us in technology, politics and the media. Along with these rapid changes, we also see quickly mounting costs, greater expectations and “heightened calls for accountability from a range of constituencies” (ACPA & NASPA, 2015, pp. 7). These calls for accountability often require student affairs professionals to advocate for themselves and their students in the language those constituencies understand and trust: data and numbers. Quantifying value in this way does not come naturally to most, but it’s an increasingly important competency for any student affairs professional to master. Many professionals would describe assessment as ‘justifying spending to secure more resources.’ However, this limited understanding highlights a dangerous theme: departure from the ability to effectively use assessment, evaluation, and research practices to demonstrate value.

According to Plano-Clark and Creswell, “armed with results based on rigorous research, practitioners become professionals who are more effective, and this effectiveness translates into better outcomes” (2015, pp. 8). This is reflective of the fast-paced change and increased focus on value in higher education. In order to quantify value successfully, professionals must know how to pursue results based on rigorous research. My desire to measure and communicate the value of higher education and career development more effectively led me to address the following outcomes: “effectively articulate, interpret, and use results of assessment, evaluation, and research reports and studies, including professional literature, facilitate appropriate data collection for system/ department-wide assessment and evaluation efforts using current technology and methods, apply the concepts and procedures of qualitative research, evaluation, and assessment including creating appropriate sampling designs and interview protocols with consultation to ensure the trustworthiness of qualitative designs, and explain to students and colleagues the relationship of assessment, evaluation, and research processes to learning outcomes and goals” (ACPA & NASPA, 2015).

My next research addressed Preferred Name Policy in Career Services. I researched professional literature about best practices, synthesized the research, and interviewed several career services professionals about their experiences. I then used those insights to identify salient themes and potential solutions. Throughout, I gathered resources from professional associations to frame my research. My presentation at Graduate Research Day addressed best practices used by professionals, insights from the institution’s president, and a plan of action for implementing the policy in our office. This experience demonstrated two key insights for me. First, I learned that a project might turn out to be larger in scope than assumed, but that flexibility can lead to even more insightful results. Second, I was reminded that the assessment, evaluation, and research process isn’t designed to provide answers. Instead, it helps frame the complexity of an issue and identify potential courses of action. This project enhanced my competence in several of the desired outcomes, but more importantly, it made a positive contribution to support students in our office. I am proud that I contributed to greater inclusivity on campus, as that is one of my guiding philosophies as a professional.

Interpretations of Existing Literature & Data

My background at UConn, which is designated as a Research One institution, informed my initial idea of research heading into graduate school. My relative inexperience in comparison to UConn Ph.D. students gave me the impression that I needed to go back to the basics and achieve mastery before I could do meaningful research. To practice, I developed a hypothetical study in which I conducted a literature review, selected appropriate research methods, and wrote up mock results (although actual data was not collected in the interest of time). I chose to look at first year first-generation college student adjustment and family attachment in culturally diverse families (attached). Throughout this project, I employed my knowledge of different methods to select a research design that complimented the purpose and goals of my project. Ultimately, I chose a qualitative approach that would have used semi-structured interviews to identify overarching themes in the data. Accordingly, I interpreted and synthesized relevant literature to appropriately situate my proposed study within the context of current research. This approach would have gathered highly relevant insights if I had completed data collection.

References:

ACPA & NASPA. (2015). Professional Competency Areas for Student Affairs Educators. Washington, D.C.: Authors.

Bingham, R.P., Bureau, D., & Garrison Duncan, A. (2015). Leading Assessment for Student Success: Ten Tenets that Change Culture and Practice in Student Affairs. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Evans, N.J., Forney, D.S., Guido, F.M., Patton, L.D., & Renn, K. A. (2010). Student Development In College: Theory, Research and Practice. 2 Ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merrill, N. (2011). Social media for social research: Applications for higher education communications. In L.A. Wankel & C. Wankel (Eds.) Higher Education Administration with Social Media: Including Applications in Student Affairs, Enrollment Management, Alumni Relations, and Career Centers. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

NACE. (2013). Professional Competencies for College and University Career Services Practitioners. Bethlehem, PA: Authors.

Plano-Clark, V.L. & Creswell, J.W. (2015). Understanding Research: A Consumer’s Guide, 2 Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Informed Decisions & Improved Outcomes

Through reflection about my level of competence in this area, I began to note that there was a missing component in my original project, since I had not articulated the value of the research. A collection of data alone, especially a hypothetical set of data, does little to articulate value to stakeholders. For research to be effective, the data needs to be interpreted and condensed into more comprehensible pieces. According to Bingham, Bureau, and Garrison Duncan, data should “be promoted and shared among individuals in an easily comprehensible form” because this allows greater accountability and transparency in decision-making, ultimately showcasing a commitment to student success. The following semester, I collaborated with my peers to develop and distribute a survey called “Attitudes about Awareness of Sexual Assault at Salem State University” for one of our courses. Following the completion of data collection, my colleagues and I analyzed the results to draw conclusions about the campus climate and awareness of the topic. We created an executive summary and infographic to synthesize and represent our work, which was provided to the institution for review (attached). The use of the executive summary and infographic made the data easier to digest quickly, which reflects the recommendations provided by Bingham, Bureau, and Garrison Duncan.

Assessment, Evaluation & Research

Career Services regularly reviews our practice to ensure that students have access to the resources they need to be successful. Over the summer, the team sent out a survey to determine if students felt that there were barriers preventing them from using our resources. Following a robust response, the team condensed the information and decided that a focus group could provide more details to inform our course of action. I developed a focus group interview protocol by downloading a report of survey results, evaluating answers, and thematically grouping results in accordance with suggestions from the NACE Professional Competencies for College and University Career Services Practitioners (2013). Once I was confident that the protocol was suitable, I co-facilitated a focus group with another staff member. We summarized the responses, which provided incredibly valuable information, and shared them with the team. The process of assessing our work as a team was particularly exciting, and we developed several innovative solutions to consider.

◄

1 / 1

►

Involving Students and Technology in Assessment

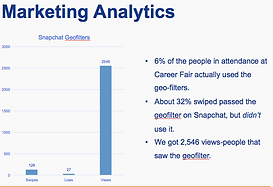

In an office that depends on student employees to function, it can be challenging to decide what tasks are appropriate to delegate. As a professional who values experiential learning and transferable skill development, it is challenging for me to gauge the optimal dissonance for students and decide their “readiness” for increased challenge and support (Evans, Forney, Guido, Patton & Renn, 2010). To establish increased confidence in their abilities, I work collaboratively with the students I supervise to observe their skill development. Although our face-to-face meetings only take place once per week, we have found technology-rich ways of staying in touch during other works times. This isn’t a stretch by any means, as it becomes increasingly common to incorporate social media into higher education. According to Merrill, “Beyond information distribution, higher education is also using social media tools to gain insight into target audiences” (2011, pp. 26). When used in assessment, this is sometimes called digital ethnography, which can be “rich in quantitative and qualitative data for the researcher” (Merrill, 2011, pp. 28). I tried this approach at the Career Fair by encouraging student employees to ask attendees to share their insights about the fair on social media. This gave student employees a fun way to practice networking, social media marketing, and data collection. One student later presented the analytics from social media posts in a staff meeting, which incorporated presentation skills development.

In the professional development segment of our weekly meetings with student employees, staff members present career development topics, which they generally preface by specifying that it will address “x, y, and z” learning outcomes. Sometimes, I try to augment the presentations with an interactive component. In this case, the cover letter presentation (attached) addresses the following learning outcomes: “students will be able to: locate the Career Services Cover Letter Guide, know the basic format of a cover letter, learn the information that goes in each paragraph, and know to use the requirements in a job description to tailor their cover letter.” By encouraging their participation in the interactive components of presentations, I align my practice with Bingham, Bureau, and Garrison Duncan (2015), who suggest implementing a “game approach” to engage staff in assessment. This method helps me evaluate their ability to articulate the importance of learning outcomes.